3 Brutal Lessons From Becoming My Parents’ Caretaker at 47

What filial piety really looks like when all the “I’m fine”s start sounding like tsunami sirens.

Hey, there.

Here’s something nobody tells you about unemployment: it doesn’t actually mean you’re not working. I’m working harder than I ever did when I had a job—except now I’m unpaid, underqualified, and somehow the primary caretaker for two people who spent my entire childhood telling me I needed to get my shit together.

(The irony is not lost on me.)

I’ve sat through enough medical appointments to earn an honorary degree in gerontology. And I’ve learned that “I’m fine” in Mandarin translates roughly to “everything is falling apart, but I refuse to admit it because that would mean I failed as a parent, a spouse, and a human being.”

It’s been a real growth year, you know?

If you’re a first-gen or 1.5-gen kid dealing with aging parents, you already know: nobody prepares you for this shit. No one tells you that being good at your job and good at keeping your mom from self-destructing requires completely different skill sets.

Here are three things I wish someone had told me before I became the unofficial crisis manager for a family that communicates primarily through guilt and half-translated text messages.

Lesson 1: “I’m Fine” Is Never Fine

You think you know your parents. You grew up translating cable bills and explaining American customs at parent-teacher conferences. You were the cultural ambassador—the bridge between worlds.

Then your mom calls and says, “I’m fine,” in that specific tone—the one that sounds like she’s standing on the ledge of a building but doesn’t want to inconvenience the fire department. That’s when you learn: you don’t know shit.

Taking action here means learning to read between the lines of every phone call. When Mom says, “Your father ate all the daikon,” she’s actually saying, I’m overwhelmed and don’t know how to ask for help. When she mentions parking the car in the driveway instead of the garage, she’s telling you Dad’s confusion is getting worse, and she’s terrified.

I spent six months ignoring the subtext. Mom would call, recite her daily complaints about Dad (his memory, his mess, his refusal to throw away junk mail because “it’s important”), and I’d offer solutions: get a home health aide, install grab bars, hire someone to sort the mail. She rejected everything. I thought she was being difficult.

Then I had to convince Dad to move into a care facility, and on the third attempt—after two failed starts and screaming matches that lasted hours—he just… sat down on the garage floor. Arms crossed, refusing to move.

This man, who’d been a military officer—who’d terrified me my entire childhood—was sitting on cold concrete like a toddler throwing a tantrum. Except it wasn’t a tantrum. He knew we were lying when we said he was “going to the doctor.” He knew something bad was happening.

The workers from the facility looked at me and shook their heads: We can’t take him like this.

So I had to get sedation pills from his doctor. I had to lie to his face. And when the van finally drove away, he was doped up and confused. Mom was hiding in the house because she couldn’t watch—I understood.

All those rejected solutions? Mom wasn’t being difficult. She was trying to avoid this exact moment: when we gave up on keeping him home and shipped him somewhere to die.

The action you need to take is this: stop waiting for permission to help.

And here’s the thing that makes it worse.

Lesson 2: You Can’t Pour From an Empty Cup (But You’ll Try Anyway)

Everyone loves that self-care quote about not pouring from an empty cup. Cute. Inspiring. Looks great on an Instagram story with a sunset background.

Here’s what actually happens: you pour from an empty cup anyway—and then resent everyone for needing you to pour in the first place.

You will run yourself into the ground trying to be the good kid—the responsible one, the fixer. Because the alternative—setting boundaries with the people who raised you—feels like betrayal.

Every Asian kid caring for aging parents knows this math. We were raised on filial piety, on the idea that we’d repay our parents’ sacrifices. But they cared for us by working themselves to the point of exhaustion. How do you tell someone who has never taken a break that they need one?

Your parents won’t notice you’re falling apart until you collapse, and even then, they might ask if you’ve been eating enough rice.

Resentment builds quietly, then all at once. One day you’re fine. The next, you’re screaming at a Sweetgreen employee because your salad’s wrong, your thirteen-year relationship is over, and suddenly it’s not about salad anymore.

No amount of therapy (which you can’t afford anyway) will rewrite decades of programming that says your needs come last.

The hard truth isn’t about being stronger or more selfless—it’s accepting you can’t fix everything. Keep pushing and you’ll break.

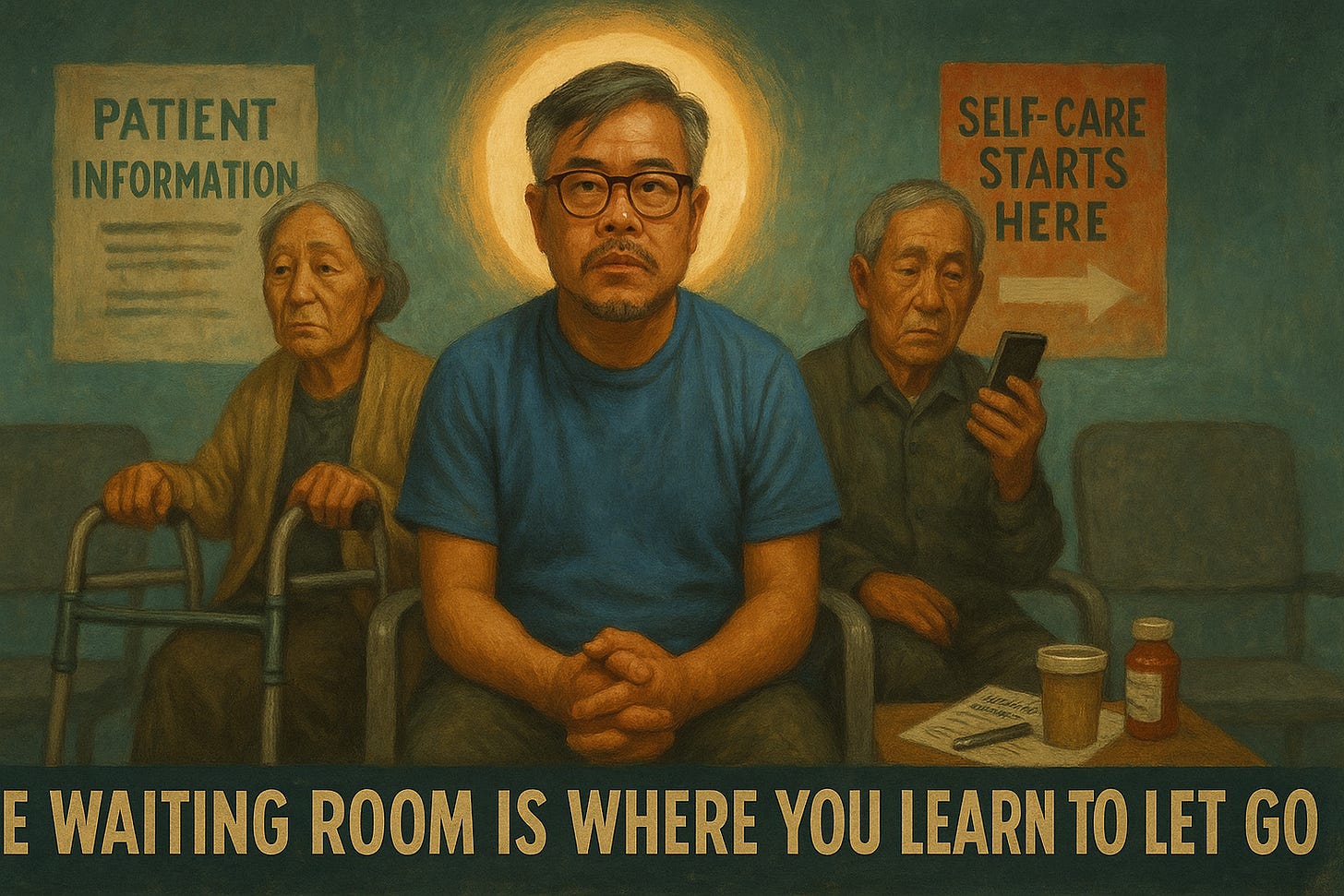

Lesson 3: The Waiting Room Is Where You Learn to Let Go

You think the hard part is getting your parents to the doctor. Wrong.

The hard part is sitting in the waiting room at Washington Hospital for two hours, watching your dad struggle to ask me why I took him to his childhood high school, while your mother sits at home with Taiwanese variety shows shouting at her at full volume, in complete denial that anything has changed in the past five years. The hard part is realizing you can’t control their health, their choices, or the inevitable decline that’s coming.

You should be doing something productive with those two hours—answering emails, updating your résumé, planning your escape route back to your own life. Instead, you’re practicing radical acceptance (or dissociation, depending on the day).

I’ve spent more time waiting: waiting for doctors to show up, waiting for Mom’s arm to heal, waiting for the attendants to push Dad into the visitation room.

Every visit to Fremont Village is the same: they wheel Dad in; my mom asks if he remembers who he is, who we are. Dad emits noises. Mom talks over him because she lost her left hearing aid—like that was ever an excuse.

This last visit, though… Jesus.

The last couple of times I went to see Dad, he was making noises at best. Dad glares at me. He looks over at Mom and flashes her this look—of betrayal, maybe disgust.

This is when I realize Mom hasn’t seen Dad in six months, and we missed his birthday—both the one he uses on documents and his actual one—thanks to some bullshit involving lunar and Gregorian calendars, I give very little fuckery over.

“莫名其妙,” I hear him audibly say to her, his face contorting. Dad’s one day of lucidity, and he uses it to argue with Mom. Of course, she doesn’t notice because of her hearing loss.

“What did he say again?” Mom turns to me, half-bemused.

“莫名其妙,” I repeat to her. It’s an idiom that means baffling or inexplicable. In the context of my parents, it means more like, what the fuck, man?

So yeah, Dad’s first words in six months? Basically “WTF.” Legacy secured.

I watch my mom’s face as everything clicks, the corners of her mouth falling, her eyes flashing, her voice rising. “Well… we didn’t come all this way to be insulted. I was injured, you know, and HE never took care of me. He’s not the one who wrote THAT LETTER, the one who…”

I take Mom by the arm and lead her out of the facility as she gets even more belligerent, apologizing to any Filipino staff I can make eye contact with. I glance back as Dad sits by himself with his back to me, stewing in his wheelchair and his rage.

By the time we’re back in my car, Mom is quiet again.

“…you okay, ma?”

“還可以啦. 我沒什麼,” she replies.

I’m fine, she says.

Nothing to worry about.

I sit there wondering how I became the adult in this situation when I still feel like I’m faking it.

Here’s what I learned waiting: you can’t save people from getting old. You can’t logic them into taking better care of themselves. You can’t fix decades of communication patterns with a single difficult conversation. All you can do is show up, translate when needed, and try not to lose yourself in the process.

And… and I start the car.

Nothing in old age is easy, it seems. I hate what you've had to deal with in helping your parents. My parents took good care of themselves and never really got to grow old. Cancer got both of them in their 60s. So while I haven't watched my parents fade mentally, I did watch them die slow, hard deaths. Life can be so brutal.

Of course, I had feelings similar to yours, even though our cultural backgrounds are different. That feeling of "they've done everything for me, how can I not be there for them?" is the same. But the toughest part is, no matter how hard we try, we can't fix what's wrong. We can try our best to help them--as I did and I know you continue to do--but we'll never fix what's wrong. Also, I felt completely unprepared for this adult stuff and really felt impostor syndrome in a big way. I think anyone who cares feels the same thing. That's life, even if we wish it weren't so.

Ernie, this was so beautiful. You're SUCH a beautiful writer.

Thanks for sharing this. I'm sorry for all the hard bits.