I’m Fine, I’m Fine, I’m Fine

Contract work, elder care, and the strange math of being professionally competent and financially panicked at the same time

The EDD website times out while I’m mid-sentence explaining why my contract ended, which feels about right.

It’s January 31st, my official last day at Intuit, and I’m sitting at my desk doing two things simultaneously: researching California unemployment benefits on Perplexity.ai, and logging into my bank account to pay my dad’s $6,665 monthly facility bill using his money.

Tab one: “In CA, can I file for unemployment because my contract ended?”

Tab two: Send a paper check using the bank account balance; transfer the balance from Dad’s account to mine.

The juxtaposition is chef’s kiss.

If the chef were having a nervous breakdown.

The Professional Humiliation Shuffle

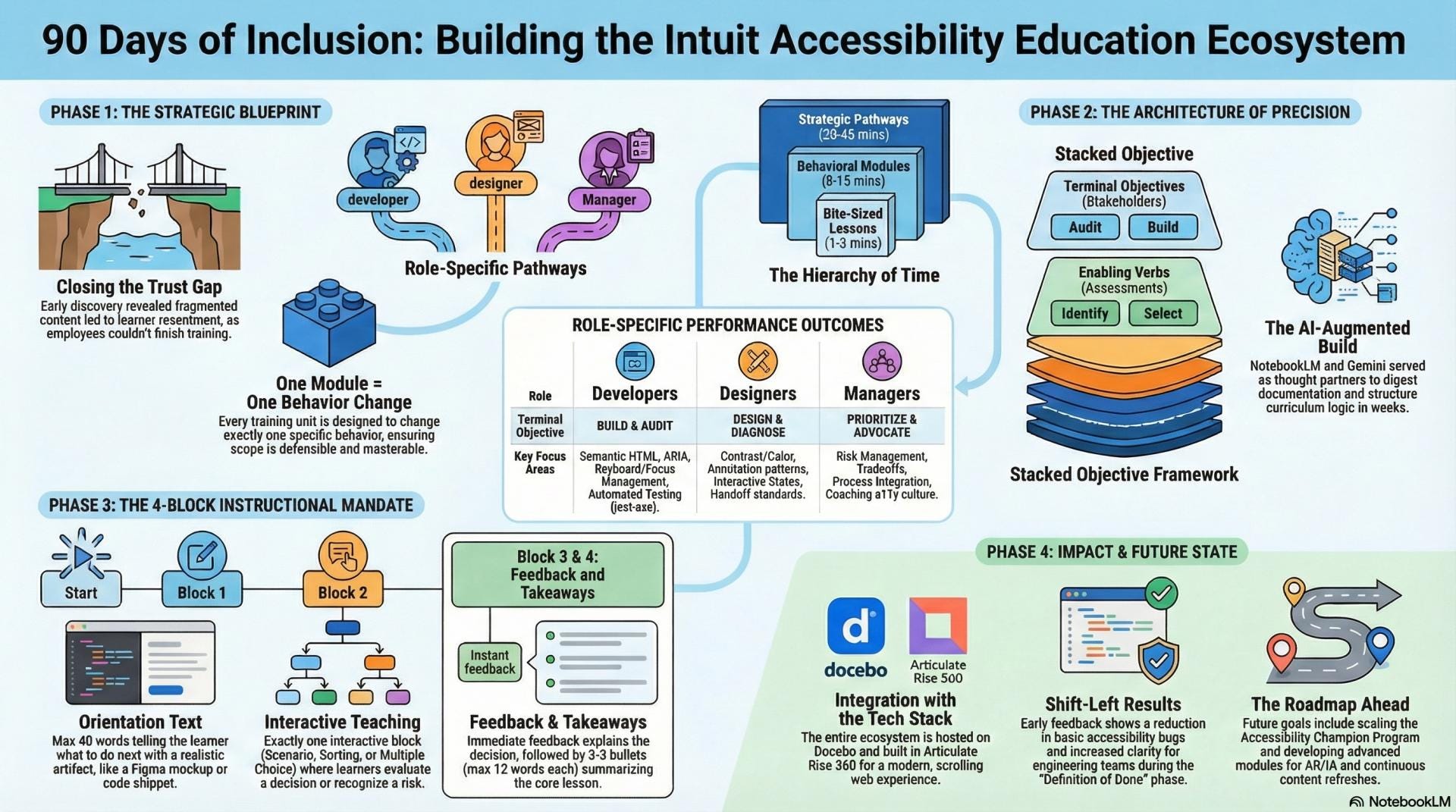

It’s 2026, and this is contract work at major tech companies: you can be skilled enough to build accessibility training courses for incoming developers, designers, and managers at a Fortune 500, trusted enough to help shape how thousands of employees learn about accessibility and WCAG 2.2 compliance, and still end up searching eligibility requirements like you’re twenty-two and just got laid off from a Jamba Juice.

The unemployment form asks for my reason for separation. I stare at the dropdown menu.

“Contract ended” feels too clinical.

“They said they really liked my work but, what can I say? The budget cycle is the budget cycle” doesn’t fit.

I pick the closest option and move on.

Meanwhile, my phone buzzes. It’s the facility—something about updating payment information. I alt-tab back to my dad’s account, watching numbers I’m responsible for flow outward.

Six thousand, six hundred, sixty-five dollars.

Every month.

Whether or not I have a next gig lined up.

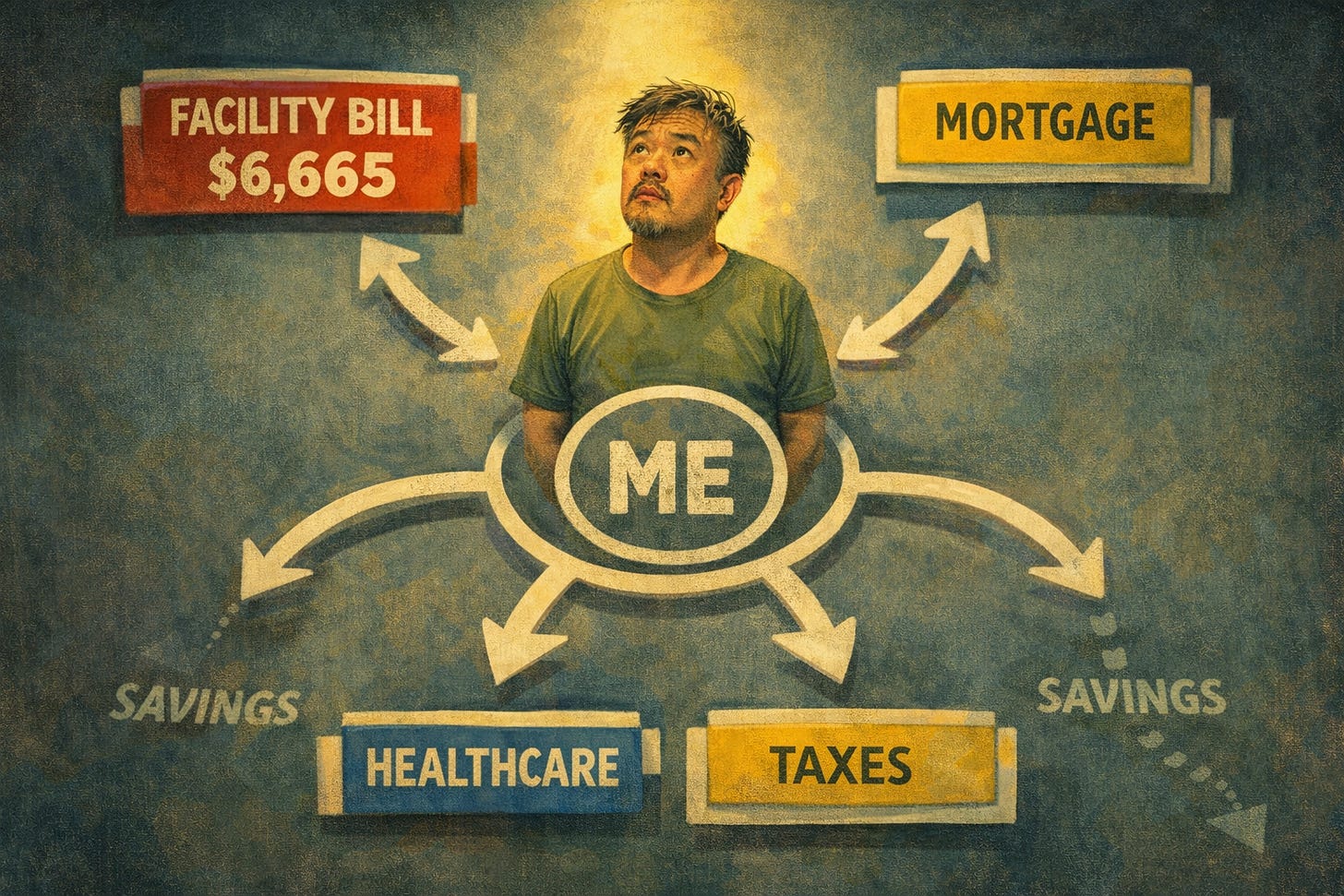

Money Flowing in All Directions Except Savings

I used to believe career progress meant emotional security about money. That was before special circumstances broke the equation.

Here are mine: a “fail-proof” industry that suddenly laid everyone off—and that has an ageism problem I’m now old enough to experience firsthand. Two aging parents—one in memory care, one requiring increasing support. A father who worked hard enough to build assets above the Medi-Cal threshold, which sounds like the American Dream until you realize it means paying $6,665 a month out of pocket until his savings drain enough to qualify. A 600-day unemployment gap that devoured whatever cushion I had. And now, a contract ending at the exact moment elder care expenses peak.

Special circumstances. I’ve got the whole collection.

This is the math they don’t teach you in computer science: your professional worth and your bank account balance are two different spreadsheets, and the formulas don’t reference each other.

The Post-Mortem I’m Already Writing

The Intuit work was good. I’m proud of what I built. But sitting here on the last day, I’m already doing the mental post-mortem, because that’s what you do when you’re a contractor—you’re always preparing the case study for the next pitch.

What would I do differently?

The courses on accessibility weren’t perfect, and I’ve had to make peace with that. It’s the natural byproduct of ADHD, multiplied by trying new things in the age of AI, and the hope that pure enthusiasm would beat out inexperience.

When you’re using language models to help generate course content, you learn fast: pick one LLM as your source of truth.

I made the mistake of mixing and matching—using NotebookLM for some modules, Gemini for others, and storing the master content in Airtable when I remembered—and the tonal inconsistencies nearly killed me during revisions. It’s like hiring three different ghostwriters for the same book and expecting them to sound like one person.

Lesson learned.

Filed away for the next gig.

Assuming there is a next gig.

The Feast-or-Famine Feature, Not Bug

Here’s the thing about tech’s contract economy that the LinkedIn hustle-porn never mentions: the feast-or-famine cycle doesn’t pause politely while you handle family responsibilities.

It doesn’t care that your dad needs a facility that costs more than some people’s mortgages. It doesn’t factor in that you’re simultaneously the family IT department, the medical advocate, the financial coordinator, and—oh right—trying to maintain your own career.

I’m forty-nine. I’ve worked at Yahoo!, founded Code for Miami, and taught at multiple bootcamps. I’d like to think I’ve built things that mattered. And yet, I’m still here, refreshing the EDD website, hoping my session doesn’t time out again before I can submit.

The thing about contract work is that it’s supposed to be a feature, not a bug.

Flexibility!

Independence!

You’re not tied down to one company’s politics or their sad birthday cake in the break room!

What the brochure doesn’t mention is that flexibility is just instability having gone through a PR makeover.

The Check Will Arrive in Five Business Days

I click submit on my dad’s bank portal—not mine, his.

I don’t have power of attorney, yet I manage my dad’s finances, which means I get to watch his savings drain toward the Medi-Cal threshold, one $6,665 check at a time.

Somewhere in the machinery of finance, a paper check will be printed, stuffed in an envelope, and mailed to the facility like it’s 1997.

The confirmation screen thanks me for my transaction.

You’re welcome.

The unemployment application waits in another tab, half-complete. I’ll finish it tomorrow, when I have the energy to hunt down pay stubs and figure out which dropdown best captures my contract ended, and I'm fine, I'm fine, I'm fine.

Tomorrow I’ll reach out to contacts, update the portfolio, and start the hustle again.

Tonight, I’ll rewatch something comforting and pretend the knot in my stomach is just hunger.

Professional pride and practical survival coexist uncomfortably. I’ve gotten good at holding both. You kind of have to, when you’re the family member who “handles things”—managing other people’s money while your own income just stopped.

The check arrives in five business days.

My dad’s next bill is due in thirty.

The unemployment form will get done when it gets done.

The math, as always, is the math.

Ernie, I wish more people were talking about this. I think this *is* the life that AI has created. And for the vast majority, it isn’t better than before.

The facility bill/unemployment form juxtaposition is devastating in its clarity. Been through similiar caregiving financials and that line about professional worth and bank balance being two diffrent spreadsheets cuts deep. The whole 'flexibility as instability in disguise' framing nails what the contractor ecomony actually feels like when life gets messy, not what LinkedIn sells it as.