American Retail Theater

“I WANT COTTON, NOT WHATEVER THIS STRETCHY THING IS.”

That was my mom six months ago in the Target underwear section, and apparently, I hadn’t learned my lesson because here we were again, this time on the Great Calendar Hunt of 2026.

The Target kiosk said “online only.” Mom said the kiosk was wrong. I said maybe we should try somewhere else. Mom said I was being lazy and asked the first red-shirted associate she could find.

“WHERE. IS. CALENDAR.” Mom was actually talking in all-caps too, ever since she lost her hearing aid at Trader Joe’s three months previous. You know, the $1100 hearing aid. Bought at full price. With an expired warranty.

“Calendars? Oh yeah, aisle B-10,” the kid said, pointing toward the back of the store.

We walked past the seasonal clearance, past the home goods, past the inexplicably large selection of throw pillows, until we reached what Target optimistically calls the “planning section.” Notebooks, pens, a few sad desk organizers, that weird thing with butcher paper where you literally have to draw your own calendar… and exactly zero wall calendars.

“WHERE ARE CALENDARS?” Mom asked, not to me, but to the universe in general—which meant she was about to ask every employee in a fifty-foot radius.

“Mom,” I say in Chinglish, “maybe the calendars really are online only—”

“Ai-ya, Don’t say 日記, that says ‘diary’ or ‘journal.’ You say 日曆. Calendar. CAL-EN-DAR.” She mocks my pronunciation like I was five years old learning English for the first time, which, let’s be honest, was peak irony given the circumstances.

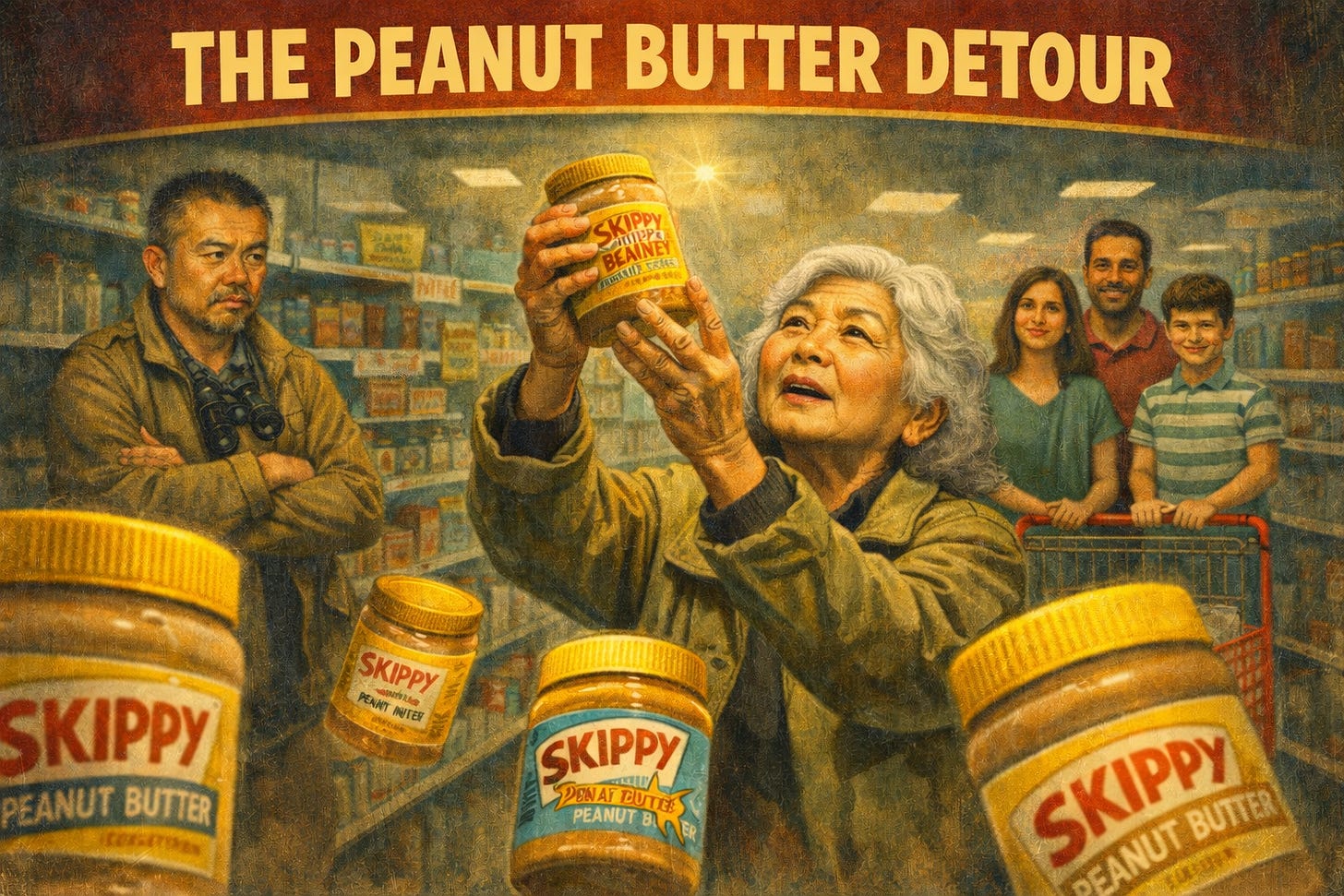

That’s when she spotted the second associate, a woman in her forties, restocking something in sporting goods. But first—and this is where I started my internal Jane Goodall documentary—Mom made a hard left into the peanut butter aisle.

”I never found the peanut butter I was telling you about. It was sweeter than the usual kind.” “SWEET PEANUT BATTER,” she announced, picking up a jar of Skippy honey peanut butter and holding it up to the fluorescent lights like she was inspecting diamonds. She shook it. She read the ingredients. She compared it to the regular Skippy. All while a perfectly normal South Asian family with a cart full of normal groceries waited behind us, shooting us the kind of looks reserved for people who treat grocery shopping like performance art.

See how his mother wanders from aisle to aisle, I heard David Attenborough’s voice in my head, speaking louder than usual because of her lack of a hearing aid, one that had been recently lost at a—

Trader Joe’s down the street, six months earlier, I whisper out loud, completing his narration.

That’s my coping mechanism, by the way. When the embarrassment hits, I detach. I become the observer, not the observed. It’s probably not healthy, but “well, at least I can blog about it” has saved my sanity more times than I can count.

But standing there in Target’s peanut butter aisle, watching my mom conduct unauthorized quality control while strangers judged us, I had a different realization: I wasn’t just observing her breaking social scripts. I was recognizing how rigidly I followed them.

Mom asked another employee, nodded seriously at whatever they said as if it made perfect sense, and we marched toward electronics. She stopped to examine a display of phone cases, picked up a clearance air freshener, and asked the electronics guy about calendars, who sent us back to customer service, who confirmed what the kiosk had said in the first place.

The whole time, I’m thinking: Just accept the online-only thing. Just buy it on Amazon like a normal person. Stop making this harder than it needs to be.

But here’s what hit me: “normal person”? According to whom? The social contract I’d internalized without questioning? The one that says you check the kiosk, accept the answer, and move on with your life like a proper assimilated American rocking the boat as little as possible?

My family is different. Like, understatement of the century, I get it—but growing up, I always assumed that difference came from being Asian. That I was weird because I was the son of Asian immigrants, and that all Asian immigrants went through the same narrative.

And it turns out that, no, plenty of Chinese, Taiwanese American families are perfectly normal. Ours is just… not.

Mom asks multiple people because she’s learned that first answers aren’t always complete answers. She checks the peanut butter because she’s buying it and wants to make sure it’s what she expects; she doesn’t care if strangers find her process inefficient because she’s not performing for strangers.

Meanwhile, I’m over here mortified that we’re not following the unspoken rules of American retail theater: be quick, be quiet, don’t bother the staff unless necessary, and for the love of God, don’t inspect grocery items like you’re conducting a scientific experiment.

That’s the thing about being a cultural translator. You don’t just code-switch between languages—you internalize entire rulebooks without realizing it. And after decades of practice, you stop questioning which rules actually matter and which ones just keep you from standing out.

But watching her ignore every subtle social cue that would normally send me into apologetic overdrive, I realized something: she’s not the one with the problem. She’s just living in the world without constantly performing for it.

We never found a physical calendar at Target. Mom bought the peanut butter, though—after checking three more jars to make sure they were all consistently honey-flavored. On the drive home, she mentioned that Half Price Books probably has calendars, which they probably do, and which we probably should have checked first.

“Next time,” she said, “we skip Target.”

“Okay,” I say. No eyerolls or ‘FINE THENs’ in that performative patience voice I use when I’m managing her. Just okay. Like we’re two people who spent forty minutes slightly annoyed and sad not to find a picture of some kitten or Half Dome on a kitchen wall.

Next time, I thought, maybe I skip the Jane Goodall routine and just let my mom be my mom. The anthropologist’s distance might save my ego, but it’s a lonely way to love someone.

My partner told me just today I should buy the one brand of instant coffee that I like online. “It’s _so_ much easier!” But no, I had to go all the way to the underground shop at the Mitsukoshi Department Store in Xinyi. Dunno why, it just _felt_ better to do it that way, to have someone hand it to me to take home.

I did wait too late for calendars; I’d rather get one from the one remaining Eslite bookstore, but alas, I, too shall have to obtain my colorful vintage travel poster calendar from the dreaded Bezos machinery.

In other words, yes, we are getting old, I suppose. The time, it flies.